How "Save the Cat Story Structure" Compares with Dramatica

By Glen C. Strathy

"Save the Cat Story Structure," described in Blake Snyder's book Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting That You'll Ever Need, is a model of story structure that was developed by a screenwriter specifically for use by other screenwriters. It is aimed at readers who want to write movie-length screenplays. Nonetheless, it has become a popular tool for writers of all types of fiction since its publication.

Depending on which genre you are writing, you may find Save the Cat story structure to be a helpful tool for working out the plot of novels or other works of fiction.

My long-held belief is that Dramatica (also developed by and for screenwriters) offers the most thorough description of story structure. However, the biggest problem with Dramatica is that its complexity makes it unwieldy for many writers. So I am always interested in approaches that simplify story theory and make it more accessible. What most aspiring fiction writers need is an approach to structure that is simple and easy to use, so they can spend less time working out their plot and focus more on other aspects of writing -- like making the characters more authentic and putting words on the page in a meaningful and engaging way.

Bottom line is that Save the Cat story structure is an accurate but simpler approach than Dramatica. Because it is simpler, it is easier to grasp and work with. At the same time, it has a few limitations and applies to certain types of stories better than others.

So let me start by briefly summarizing both Dramatica and Save the Cat and then discussing the differences between them.

Dramatica Story Structure

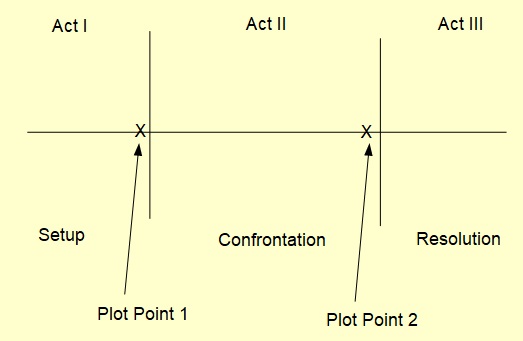

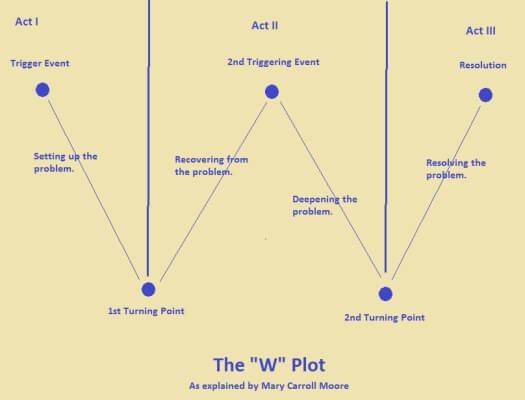

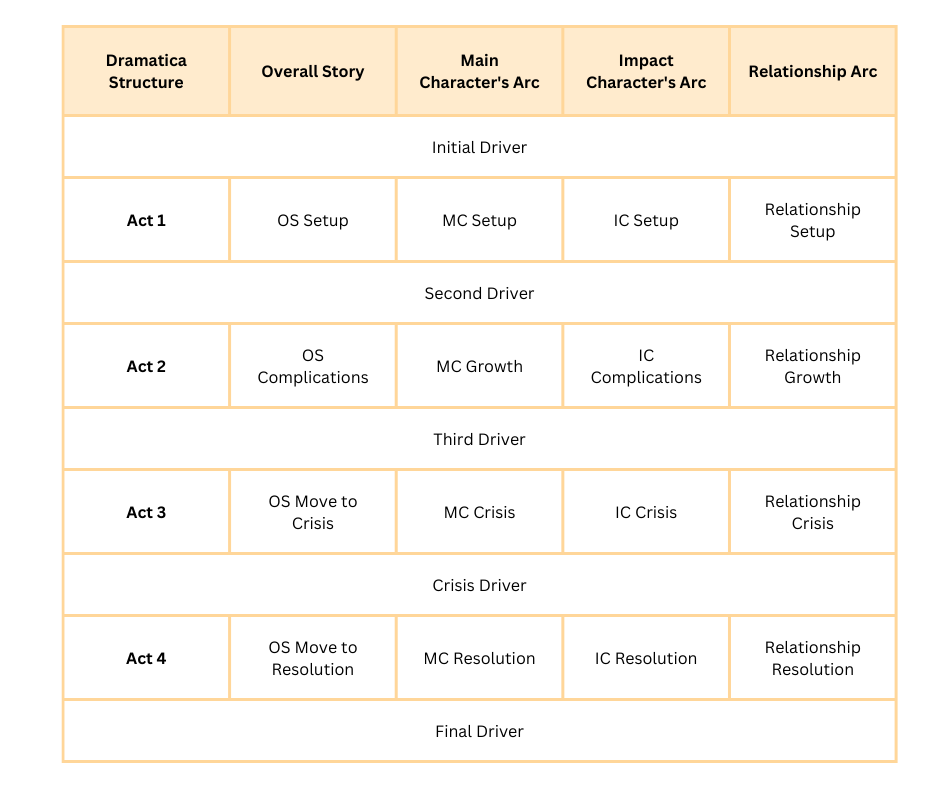

I believe a four-act structure is the simplest, clearest way of understanding stories. In the Dramatica model, each of the four acts begins and ends with a major turning point, called a "Driver." In the case of a fully-developed story, four main throughlines or arcs will unfold from beginning to end:

- The Overall Story, which affects or involves most of the characters and concerns the story problem.

- The Main Character Arc, which concerns the main character's inner conflict and growth.

- The Impact Character Arc, which concerns the story of how the impact character influences the main character (and therefore feeds the main character's inner conflict).

- The Relationship Arc, which follows the progress of the relationship between the main and impact characters.

Each arc follows this basic pattern: setup --> complications --> crisis --> resolution

Dramatica calls the four stages "signposts."

All the other story points (which are too numerous to cover in this article) appear in scenes that fall within these four arcs.

Here's how the Dramatica model looks visually:

Dramatica Story Structure

Dramatica Story StructureNote the above table presents the structure of a story neatly, but in an abstract and generalized way. The model gives the writer a lot of flexibility when it comes to storytelling.

For instance, Dramatica says that a story point must be illustrated (included in the story) so that the reader appreciates it. However, the amount of space on the page you need to illustrate a story point can vary a lot. Sometimes, a story point can be illustrated with only a brief line of dialogue. With other story points, you may write several chapters to illustrate them well enough for the reader to appreciate their significance. A story point can also be illustrated multiple times in different ways, if necessary.

You will notice that the Dramatica model is only partially linear. That is, the order in which the various parts of the story appear isn't completely rigid. Obviously, you wouldn't put the resolution of an arc before the crisis, chronologically, because that would deflate the emotional tension in the story. The drivers will also appear chronologically in the order shown. However, a writer can choose different ways of arranging events and story points around the drivers and within the acts. Also, some stories narrate the events in a non-chronological order. Only in hindsight can the reader understand how they relate to each other on the timeline.

As an Amazon Associate, this site earns if

you purchase these books.

Dramatica: A New Theory of Story

by Melanie Ann Philips and Chris Huntley

Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You'll Ever Need

Save the Cat Story Structure

Snyder uses a three-act structure in his book Save the Cat, but there is really no difference between three and four-act models except for where you divide the acts. Three-act models have the same number of drivers. They simply put the third driver in the middle of the middle act and call it the "midpoint." For ease of comparison, I've translated the Save the Cat story structure into a four-act model below.

Another difference between the Save the Cat story structure and Dramatica is that Save the Cat does not distinguish between the four major arcs. This doesn't mean they are omitted. Snyder blends them into one linear sequence of story events. However, the Save the Cat story structure does not prompt you to develop each arc fully the way Dramatica does.

The Save the Cat story structure has fifteen different parts or "beats" that appear in a fixed, linear order. Because the model is intended to aid with writing feature length screenplays (which are quite short compared to novels), Snyder recommends fixed lengths for each beat. Obviously, if you are writing a novel you would use the page number recommendations as a guide to the relative lengths of each beat rather than adhere to them rigorously.

Another key difference should be noted...

"Save the Cat" Describes Stories with Happy Endings Only.

Most Hollywood movies have happy endings. The villain is defeated. The guy gets the girl. The lost child is reunited with her parents. Etc. Save the Cat is a model designed to help you write those kinds of stories.

Plenty of stories do not have happy or entirely happy endings. Some are tragedies. Some are personal tragedies (or comi-tragedies). And some are personal triumphs (or tragi-comedies). Snyder mentions such stories in passing, but doesn't go into great detail about them. Such stories require a slightly different structure, which Dramatica takes into account. (See this article on plot development.)

But if you are writing a story with a happy ending, as is common in many genres, Save the Cat offers a more straightforward approach.

So let's look at the fifteen beats in a Save the Cat story.

The 15 Beats in a Save the Cat Story

1. Opening Image: This should really be called the start of the Setup. The story begins by showing the main character and the world he/she lives in as they are before the events of the story get underway.

2. Theme stated: The thematic premise of the story appears in the opening scene or close to it.

3. Setup: The opening pages will continue to introduce characters, the story goal (to use a Dramatica term), the main character's problem, etc. Snyder suggests including "six things that need fixing" -- six issues or needs of the main character that will be addressed as the story progresses. (This is a good tip. If the reader can see these six things as needing to be fixed, they will want to keep reading to find out if and how they are fixed.)

4. Catalyst: This is the event or turning point that causes the story to happen by disrupting the status quo. It's what Dramatica calls the Initial Driver. It may be the appearance of a new threat, a new opportunity, or some other event that sets in motion a chain of events.

I should note that the Catalyst or Initial Driver does not appear at this point in all stories, as Snyder suggests. In some stories it happens long before the main character is introduced (sometimes in a prologue or a first chapter that feels like a prologue). In other stories, it is told in flashback later on, or as some character's recollection. Some stories hide the catalyst for a time to create mystery. The reader sees characters reacting to the catalyst, but not the catalyst itself. For instance, in Star Wars: A New Hope, the catalyst is the theft of the Death Star plans by the rebels. But the movie doesn't show this event. Instead it begins with the Empire's reaction -- a desperate effort to recover the plans. We know the theft happened only through a line of dialogue.

5. Debate: The main character wrestles with the question of how to react to the catalyst. The debate ends with the main character deciding on a plan of action, such as Frodo deciding to take the ring to Rivendell, or Luke Shywalker deciding to go with Obi wan Kenobi.

6. Break into Two. This is the turning point that leads into the second act. It is what Dramatica calls the Second Driver. It is the event where, in a sense, the hero leaves the old world behind and embarks on a new journey.

7. The B Story: Here Snyder recommends beginning the Relationship Arc. One must assume the impact character is introduced at this point or close to it as well.

I should note that not every story waits until act two to begin the Impact Character and Relationship arcs. Many romance novels introduce the love interest (i.e. the impact character) in the first chapter, or even the first page. Many other stories begin on the day the main character meets the impact character. In fact, Dramatica would recommend beginning all four arcs in act one. However, other stories do wait to this point to introduce the impact character and many other secondary characters. It depends somewhat on the genre and someone on what feels right for the particular story.

8. Fun and Games. This is what Joseph Campbell calls "The Road of Trials." In an adventure story, it is the adventure itself, a journey through an undiscovered world. In a romance story, it is the romance -- the process of forming a romantic relationship. In a Star Trek story, it would be the exploration of an alien world or society. In a Horror, it would be the part where the heroine starts experiencing scary encounters with the supernatural. In a four-act story, it is act two.

9. Midpoint. This is the third major turning point or driver. Snyder correctly notes that each driver is often the opposite of the one before and after. For instance, if the story has a happy ending, crisis driver will be a "dark before the dawn." The midpoint will then be a "false victory," (In a tragedy, the crisis will show the protagonist "on top of the world," before disaster hits. So the midpoint will usually be a "false defeat.")

10. Bad Guys Close In. This is the build toward the crisis. In a story with a happy ending, things will be getting worse for the protagonist in this phase.

11. All is Lost. This is the part of the story where things are "darkest before the dawn." Snyder offers a good tip here by suggesting that this moment often has a "whiff of death." Either a character will die or there will be a hint of something approaching death. This is the first part of the Crisis Driver, the really big turning point of the story. (Not always is the crisis driver broken into two parts to sandwich the next beat, but it often is.)

12. Dark Night of the Soul. This is what Dramatica calls the main character's personal crisis. (It often feels as though the crisis is temporarily interrupted so the personal crisis can happen.) Essentially, when the main character sees that everything seems hopeless, he will turn inward and reflect on how his approach to solving the problem has failed and perhaps he needs to change. He then has a personal breakthrough or epiphany. He finds a new approach, a new idea etc. that will solve the problem.

This is another area where Dramatica offers more possibilities. For instance, Dramatica notes that not every main character resolves his personal crisis by changing. (Something Snyder disagrees with.) Sometimes the main character wins by doubling-down on his existing approach. Characters who choose this option are called "steadfast characters."

Also, Dramatica notes that the main character's dilemma here is generally between sticking with his initial approach (which we saw in the setup of the story) and adopting the approach represented by the impact character. It is important to have the impact character provide the main character with an example of a different approach throughout the preceding events. In that way, the impact character makes the main character doubt himself. So when the main character reaches this crisis, he can realize that perhaps the impact character was right all along and he need to start taking the impact character's approach.

13. Break into Three. Okay, Snyder calls this beat "Break into Three" because it begins act three in a three-act structure. In a four-act structure, you could call it a "break into four." It can be considered the second part of the crisis driver. The important thing to remember is that the final act of the story begins here. If it looked as though "all is lost" before, this is where the main character takes charge of the situation and starts winning.

(Note: Between beats 13 and 14, many stories build toward the final driver via a sequence of events.)

14. Finale. This is what Dramatica calls the Final Driver. It is the hero's triumph, the event that decisively shows the story goal is achieved, and the threat is ended. Snyder's description combines this with the resolution of the Relationship arc (e.g. hero gets the girl), though I think it is often better to consider them as separate events.

15. Final Image. This is the last look at the story world so the reader can see that everything has changed and the world is better off. This is what Dramatica would call the Outcome.

Dramatica suggests that the final act should also need to show the resolution of the other arcs. For example, is the main character happier and better off in the end because of how he resolved his inner conflict? Is the relationship intact? Has the impact character changed or remained steadfast?

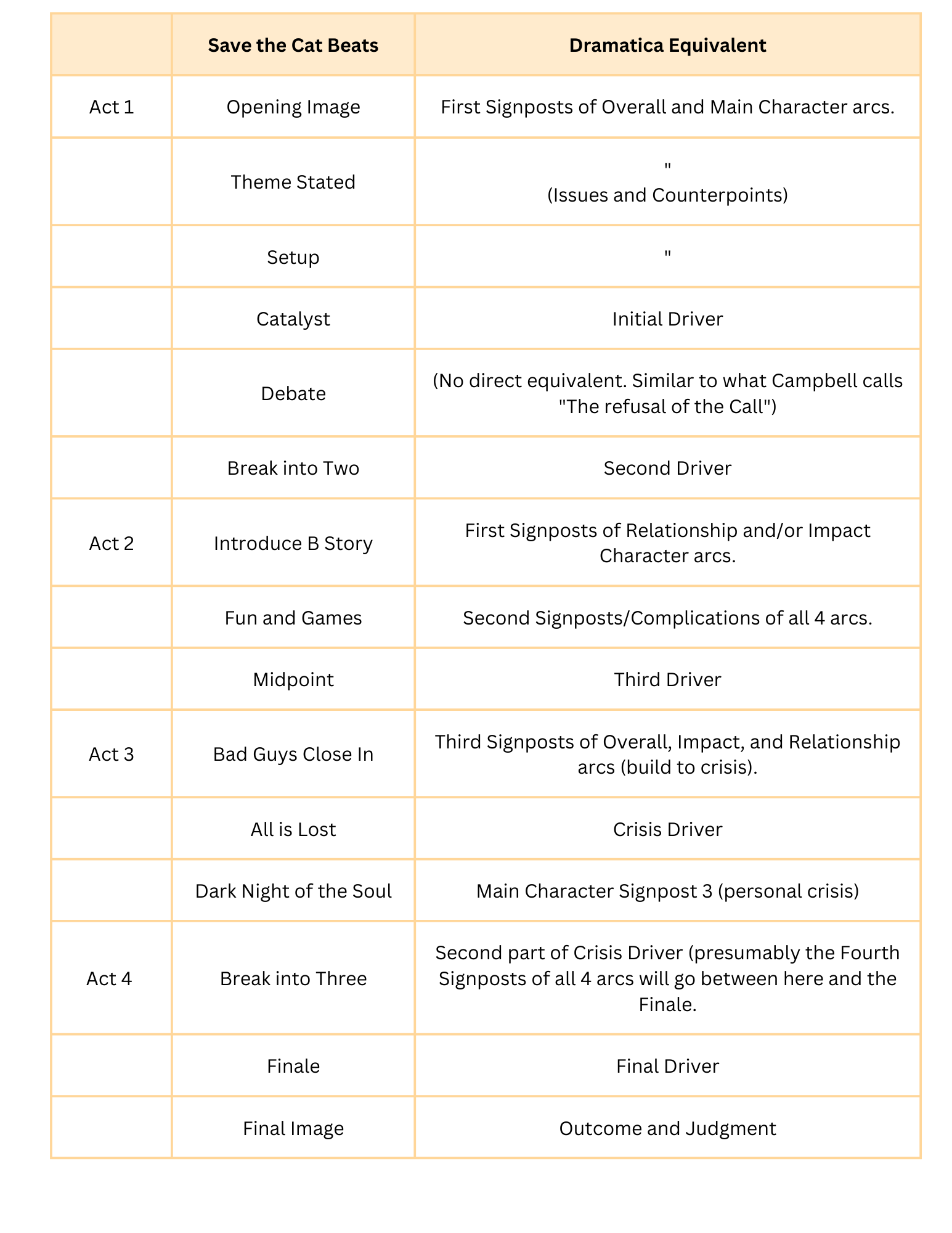

The table below summarizes the Save the Cat story structure model, and gives the equivalent Dramatics terms for each of the fifteen beats.

"Save the Cat" Story Structure Compared with Dramatica

"Save the Cat" Story Structure Compared with DramaticaOther Help

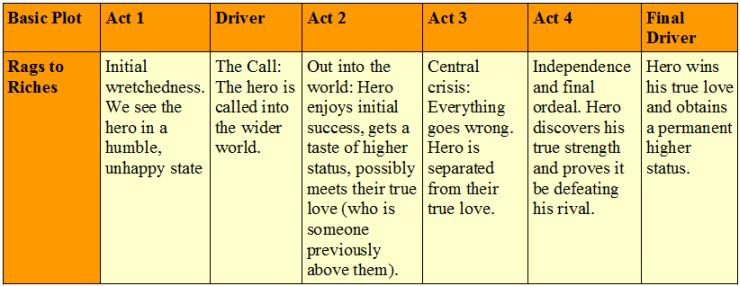

Snyder's book, Save the Cat, has many other tips, you may appreciate. For instance, Snyder discusses 10 types of stories, many of which are similar to Christopher Booker's basic plots. He presents a simple approach to storyboarding, which you could easily apply to writing novels or other forms of fiction. And he offer many tips on both fiction writing and screenwriting in particular.

- Home

- Story Structure

- Save the Cat