The Seven...Actually Nine Basic Plots According to Christopher Booker

By Glen C. Strathy

Continuing our discussion of The Seven Basic Plots by Christopher Booker, this page presents a brief outline of the plots themselves. (For more detailed discussion and examples, you should probably read the book.)

As an Amazon Associate, this site earns

if you purchase this book

after clicking this link...

In the previous article, we noted that Booker actually discusses nine archetypal plots, but only really approves of the first seven. We're going to look at all of them here briefly, partly because we think they have all been successful and partly because its good for writers to be familiar with all of them.

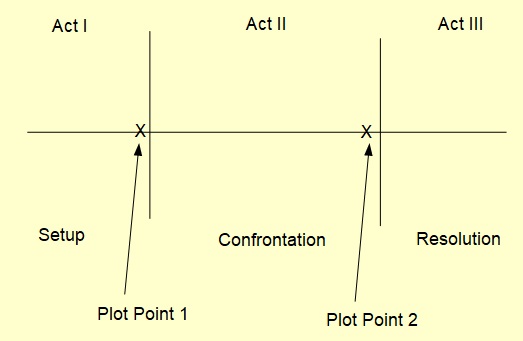

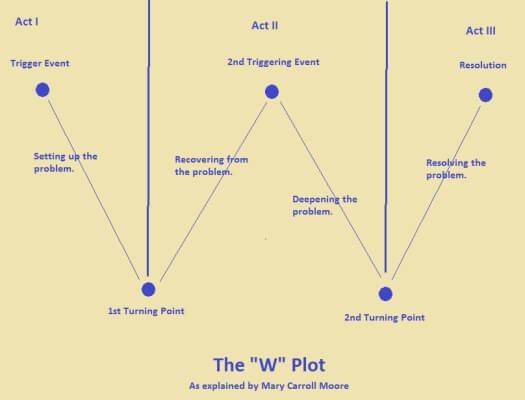

Also, we noted that, although Booker argues that the basic plots all follow a five-stage structure, it is easier to reconcile his theories with those of others by presenting them in terms of a four-act structure, with the terminals of each act marked by an event called a driver or turning point. Of the five drivers found in a four-act structure, Booker only pays attention to two of them: The Call (which is either the first or second driver) and the Final Driver (which Booker gives various names to, depending on the archetypal plot. We'll omit the others too, for simplicity's sake.

So, without further ado, here are the nine basic plots...

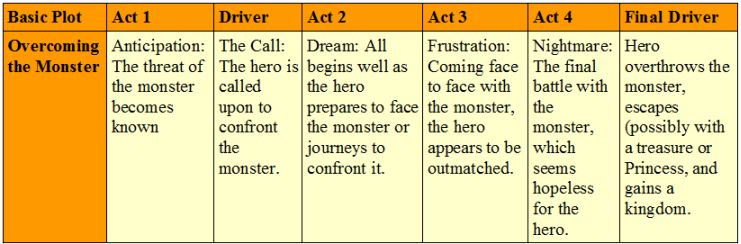

1. Overcoming the Monster

Overcoming the Monster stories involve a hero who must destroy a monster (or villain) that is threatening the community. Usually the decisive fight occurs in the monster's lair, and usually the hero has some magic weapon at his disposal. Sometimes the monster is guarding a treasure or holding a Princess captive, which the hero escapes with in the end.

Examples: James Bond films, The Magnificent Seven, The Day of the Triffids,

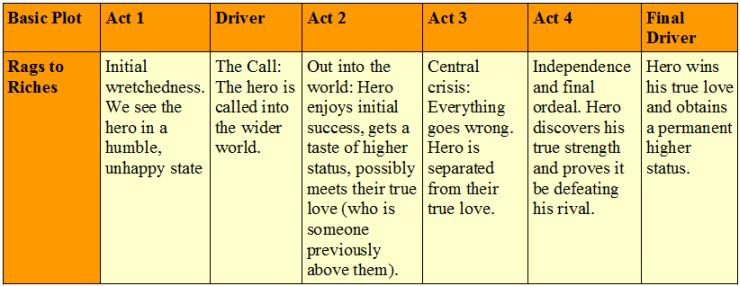

2. Rags to Riches

The Rags to Riches plot involves a hero who seems quite commonplace, poor, downtrodden, and miserable but has the potential for greatness. The story shows how he manages to fulfill his potential and become someone of wealth, importance, success and happiness.

Examples: King Arthur, Cinderella, Aladdin.

As with many of the basic plots, there are variations on Rags to Riches that are less upbeat.

Variation 1: Failure

What Booker calls the “dark” version of this story is when the hero fails to win in the end, usually because he sought wealth and status for selfish reasons. Dramatica (and most other theorists) would call this a tragedy.

Variation 2: Hollow Victory

Booker's second variation are stories where the hero “may actually achieve [his] goals, but only in a way which is hollow and brings frustration, because he again has sought them only in an outward and egocentric fashion.” Another way to describe this would be a comi-tragic ending or personal failure. In Dramatica terms, it's an outcome of success, but a judgment of failure since the hero fails to satisfactorily resolve his inner conflict.

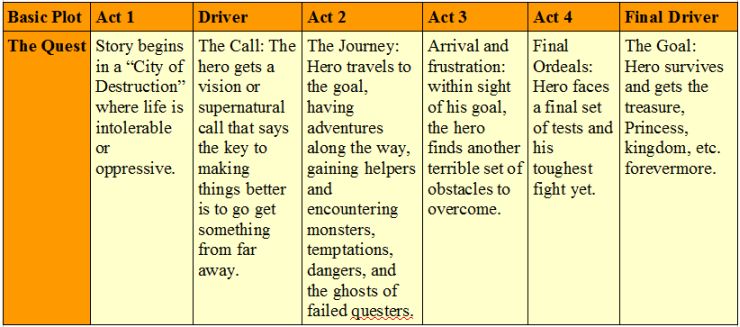

3. Quest

Quest stories involve a hero who embarks on a journey to obtain a great prize that is located far away.

E.g. Odyssey, Watership Down, Lord of the Rings (though here the goal is losing rather than gaining the treasure), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

Other variations on this basic plot include stories where the object being sought does not bring happiness. For example, Moby Dick, Raiders of the Lost Ark.

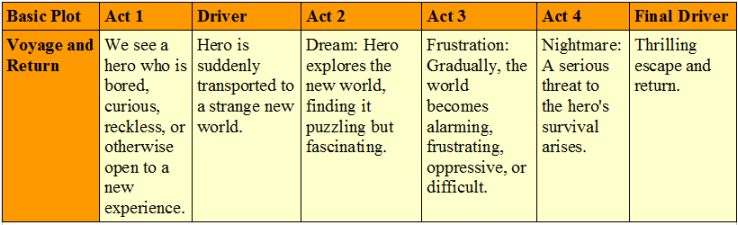

4. Voyage and Return

Voyage and Return stories feature a hero who journeys to a new world that at first seems strange but enchanting. Eventually, the hero comes to feel threatened and trapped in this world and must he must make a thrilling escape back to the safety of his home world. In some cases, the hero learns and grows as a result of his adventure (Dramatica would call this a judgment of good). In others he does not, and consequently leaves behind in the other world his true love, or other opportunity for happiness. (Dramatica would call this a judgment of bad)

Examples include: The Wizard of Oz, Coraline, Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver's Travels, Lord of the Flies.

5. Comedy

Here's where things get confusing.

Traditionally, comedy has been defined in several ways.

- As any story that ends happily. In Dramatica terms this means that the story goal is obtained (outcome=success) and the main character has satisfactorily resolved his inner conflict (judgment=good).

- As a story which is humourous or satirical.

- With New Comedy or Romantic Comedy: as a drama about finding true love (usually young love). Traditionally these stories have ended in marriage.

Booker makes a valiant attempt at a better definition of comedy, but finds he cannot apply the same plot structure to it as with the other basic plots. Instead, he loosely defines Comedy in terms of three stages:

- The story takes place in a community where the relationships between people (and by implication true love and understanding) are under the shadow of confusion, uncertainty, and frustration. Sometimes this is caused by an oppressive or self-centred person, sometimes by the hero acting in such a way, or sometimes through no one's fault.

- The confusion worsens until it reaches a crisis.

- The truth comes out, perceptions are changed, and the relationships are healed in love and understanding (and typically marriage for the hero).

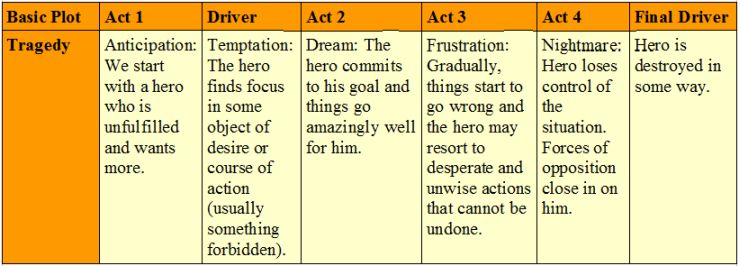

6. Tragedy

Tragedy, along with Comedy, is usually defined by its ending, which makes these two unlike the other basic plots. In Dramatica terms, a tragedy is a story in which the Story Goal is not achieved (outcome=failure) and the hero does not resolve his inner conflict happily (judgement=bad).

Booker's description of this plot is close to that of the classic tragedies (Greek, Roman, or Shakespearean).

Examples: Macbeth, Othello, Dr. Faustus

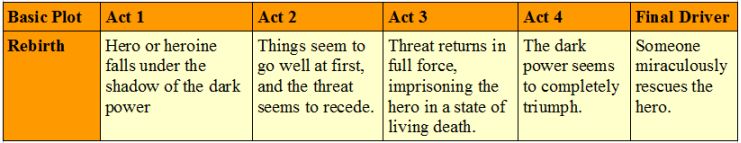

7. Rebirth

Rebirth stories show a hero (often a heroine) who is trapped in a living death by a dark power or villain until she is freed by another character's loving act. As with Comedy, Booker's outline of this plot is sketchy.

One of the big problems with this plot is that the hero does not solve his own problem but must be rescued by someone else, and therefore can avoid resolving his inner conflict. This is why many women hate certain fairy tales: the heroines are so passive.

The Disney version of Beauty and the Beast solves the problem by making Belle the main character (she rescues Beast). Though Marley intervenes to rescue Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, Scrooge ultimately chooses to change and therefore saves himself. (Hint: any new version of Sleeping Beauty should make the Prince the main character.)

Examples include Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, A Christmas Carol, Beauty and the Beast, The Secret Garden

Basic Plots Booker Dislikes...

The last two basic plots are ones which Booker clearly sees as inferior, because they are less about the main character embracing his feminine side.

8. Mystery

First, he defines Mystery as a story in which an outsider to some horrendous event or drama (such as a murder) tries to discover the truth of what happened. Often what is being investigated in a Mystery is a story based on one of the other plots.

Booker dislikes Mysteries because the detective or investigator has no personal connection to the characters he's interviewing or the crime he's investigating. Therefore, Booker argues, the detective has no inner conflict to resolve.

This may be true of some Mysteries. However, many Mystery stories create inner conflict for the detective, often in the form of a moral dilemma. Does he stick doggedly to his definition of justice or is he forced to reconsider how justice is defined? Does he find himself developing a relationship or feelings that conflict with his pursuit of justice? Chinatown, is one example of a Mystery in which the detective wrestles with a moral dilemma. Murder on the Orient Express and The Maltese Falcon are two more (just to name some classics).

What is true is that detectives in most Mystery series do not change over the course of a story. They remain steadfast. They may be tempted to change, but to change would be a mistake that would let the murderer go free. So instead they resolve their inner conflict by doubling down or reaffirming their initial approach, often at great cost to their feelings. This is necessary so they are the same person at the start of the next Mystery. A story in which the detective changes is usually the last in the series.

9. Rebellion Against 'The One'

The last of Booker's basic plots, Rebellion Against 'The One' concerns a hero who rebels against the all-powerful entity that controls the world until he is forced to surrender to that power. The One may represent God, society, community, government, family, etc.

The hero is a solitary figure who initially feels the One is at fault and that he must preserve his independence or refusal to submit. Eventually, he is faced with the One's awesome power and submits, becoming part of the community again.

In some versions, the One is portrayed as benevolent, as in the story of Job, while in others the reader is left convinced it is malevolent, as in 1984 or Brazil. These darker versions seem to be what make Booker less than keen on this basic plot.

Though Booker doesn't mention it, a common variation is to have the hero refuse to submit and essentially win against the power of the One. In The Prisoner, the hero eventually earns the right to discover that the One is a twisted version of himself, after which he is set free. In The Matrix, Neo's resistance eventually leads to a better world. Another example is The Hunger Games series, where Katniss's continued rebellion eventually leads to the downfall of both the original tyrant and his potential successor, resulting in the world order ending and greater freedom for all.

- Home

- Story Structure

- Basic Plots

See the previous article for more discussion of Booker's The Seven Basic Plots.