Comparing the Story Theories of Michael Hague and Dramatica

By Glen C. Strathy

Michael Hague, author of Writing Screenplays that Sell is one of the top story structure gurus in Hollywood. Some months ago, I had the opportunity to attend his one-day workshop called “Story Mastery.”

Naturally, I wanted to see whether Hague had ideas about story that differed from or added to Dramatica (my favourite story model). Essentially, there were two main areas where I feel novel writers can benefit from comparing the two approaches: Story Goal and Plot Structure.

Michael Hague on Story Goals

Like Dramatica, Michael Hague believes the organizing principle of a good plot is a Story Goal, an objective pursued by the protagonist that affects or involves most of the characters in the story.

However, Michael Hague gives a very useful tip when it comes to choosing a story goal. He says that a good goal is one that can be visualized. You should be able to picture in your mind what the main character's life will look like at the end of your story, and that image will prove whether the goal has been achieved.

To take some examples from film, it would not be enough to see Luke Skywalker blow up the Death Star at the end of Star Wars: A New Hope. The audience needs to see the awards ceremony to know that Luke's victory has changed his life for the better. In Casablanca, it would not be enough to see Richard Blaine decide to help Ilsa or even shoot Major Strasser. The audience needs to see him walking away from Casablanca and beginning “a beautiful friendship” with Renault. Similarly, Love, Actually ends with multiple scenes of people hugging, and the last shot of A Christmas Carol shows Tiny Tim running without crutches.

Although Michael Hague confined his talk to films with happy endings, I believe the same principle holds true for stories in which Story Goal is not achieved. For instance, in Harold and Maude, Harold's mother fails to get Harold to lead a life of adult responsibility, and this is illustrated by the final shot of Harold strolling along by the sea, playing the banjo.

Of course, Michael Hague, like the creators of Dramatica and other story structure gurus, bases his ideas primarily on film stories, and film is a visual medium. If you can't photograph a story element, you generally can't communicate it to a film audience. Films are almost all “show” rather than “tell.”

In novel writing, which is an expression in words rather than pictures, “show, don't tell” is also a very important technique. Rather than just writing “and they all lived happily every after,” your novel will likely be stronger if you can write a scene at the end of your novel that illustrates that happy life.

There are exceptions to this principle, to be sure. For example, at the end of 1984 when the protagonist fails to maintain his resistance to the state and comes to love Big Brother, the moment of transformation is told more than shown. But generally, showing is better.

Michael Hague points out that most Hollywood films (and by extension genre or plot-based novels) generally revolve around five goals:

- to escape

- to stop something from happening.

- to deliver something of value to where it's needed

- to retrieve something of value and return it to the right people/place (includes rescue stories)

- to win something (a contest, game, love, respect etc.)

Of these five, Hague argues that the goal “to win” is used most often.

Melanie Anne Phillips, co-creator of Dramatica, argues that the most common story goal is “obtaining,” which is really the same thing when you consider ...

to escape = to obtain freedom (e.g. Escape from New York, Casablanca)

to deliver = to dis-obtain something (e.g. Lord of the Rings)

to retrieve and return = to obtain and dis-obtain (e.g. any of the Indiana Jones films)

to win = to obtain victory, love, honour, a prize, success, status, or something else.

As for the 2nd type of goal Michael Hague mentioned, “to stop something happening,” Dramatica would call this a goal of either The Future (if it's a potential future event) or Progress (if it's a process that needs to be halted or changed).

While Michael Hague didn't explicitly exclude other types of Story Goals, he didn't mention them either. Dramatica, on the other hand, claims that all Story Goals (at least in Western culture) fit into one of 16 types:

Activities: Obtaining, Doing, Understanding, Gathering Information

Situations: Present, Past, Future, or Progress

Attitudes: Memory, Impulsive Responses, Desires, or Contemplation

Psychological Change/Manipulation: Playing a Role, Being, Developing a Plan, or Conceiving an Idea

Whether you see Dramatica's list as expanding or limiting the range of possible goals is a matter of individual perspective. Personally, I think the list is useful if it suggests new possibilities to you.

If you want to write a genre or plot-based novel, then you might consider using one of Hague's 5 Goals, or some variation of Obtaining. For instance, your crime novel might have a goal of catching the murderer or rescuing the kidnapped child.

On the other hand, your novel could be about discovering who did the crime and how (gathering information), understanding why the crimes are occurring, or crippling a crime syndicate (doing).

On the other hand, if you are writing literary fiction or a character-based novel, you might consider a Goal related to Attitude or Manipulation. Perhaps your protagonist will be grappling with a memory or coming to terms with a hidden desire, or prejudice. Perhaps the conflict will arise due to characters who manipulate each other or who think in in different ways.

An Easier-to-Understand Plot Structure

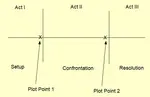

Once you have chosen a Story Goal, Hague's sees that the pursuit of that goal as evolving over a six-stage plot structure, with a turning point between each stage. Here's my recollection of how this looks:

Stage 1: Setup (the hero's life before the story begins)

Turning Point 1: the hero decides to take advantage of a New Opportunity

Stage 2: the hero finds himself in a New Situation

Turning Point 2: a Change of Plans

Stage 3: Progress towards the goal

Turning Point 3: the Point of No Return

Stage 4: Complications and Higher Stakes

Turning Point 4: Major Setback

Stage 5: the Final Push

Turning Point 5: the Climax (where the hero wavers before deciding to do what must be done to achieve the goal)

Stage 6: the Aftermath (the hero's new life)

At first glance, this looks quite different from Dramatica's structure, which is based on four throughlines, each of which has four signposts, for a total of 16 events.

However, Hague's scheme is actually quite similar, even if somewhat simplified.

Hague's Stages 2, 3, 4, and 6 correspond to the four signposts of the Overall Story in Dramatica. This is not surprising, since this four-part structure has been dominant since the days of classical Greek drama. Modern story theories differ in the ways they add emotional depth via the main character's internal conflict.

At one point in Michael Hague said that the main character's journey also progresses throughout the story, but because these stages happen simultaneously with the overall story, there was no need to discuss them separately – with two exceptions.

Stage 1 and Stage 5 in Hague's scheme are specifically related to the main character's journey. They correspond closely to Signpost 1 and 3 of Dramatica's Main Character Throughline. Hague has, in a sense, ignored Dramatica's other two throughlines (those of the Impact Character and the Subjective Story) and omitted (or perhaps integrated) the Main Character's second and fourth signposts.

As for the Turning Points Michael Hague describes, they seem to correspond to what Dramatica calls Drivers – decisions or actions which instigate the next stage in a story.

Overall, Hague's model is much simpler than Dramatica and I suspect most writers would find it easier to understand and use. You can grasp Hague's model fairly quickly. And if your interest is primarily in Hollywood-style, plot driven, genre fiction, you may need little else. Dramatica, on the other hand, has a very steep learning curve. It typically takes weeks or months to come to terms with Dramatica in its entirety.

In the long run I feel Dramatica offers ways to add more layers of emotional depth and helps you create a broader range of stories. Nonetheless, you might want to check out Hague's book Writing Screenplays That Sell. Many of the insights regarding story structure apply equally to novels.

- Home

- Story Structure

- Michael Hague