How Using Dramatica Theory Might Help You Write Better Stories

By Glen C. Strathy

I've been using dramatica theory and writing about it for a long time on this site without explaining exactly what it is. So let me correct that. Dramatica theory is a theory of story structure that was developed and

published by Melanie Anne Philips and Chris Huntley, two film

students/screenwriters, in 1993. The theory is also the basis of a

software program by the same name.

Though Phillips and Huntley

based Dramatica mainly on an examination of successful screenplays, the

theory applies to all media of story telling, including novels, comic

books, short stories, and plays. Since its publication, many fiction writers have been using dramatica theory as well as the

software to help them improve their story structure.

Using dramatica theory is no easy feat. The learning curve is steep. But dramatica offers many

unique insights and is arguably more complete in its understanding of

story dynamics and structure than traditional literary theories. It also

differs in looking at stories more from a writer's perspective than a

reader's. In other words, it's concerned with how a writer constructs

meaning rather than the cultural significance of stories.

Unfortunately,

it's impossible to explain Dramatica theory "in a nutshell," though many of the

articles on this website are an attempt to describe aspects of the

theory in a way that is practical without becoming overwhelming, and to show how it dovetails with and expands upon simpler story models.

But let's see if I can give outline the basics of what sets Dramatica theory apart...

What are "Story" and "Characters" (according to Dramatica Theory)?

Dramatica theory regards every story as a model of a mind attempting to solve a problem or reach an equilibrium.

Stories are about problems. Something is wrong in the world or in someone's life, and this sets various forces in motion in an effort to correct this problem and create a resolution -- a harmony, balance, or "happy ever after." Of course, some stories find a final balance or resolution in the form of an "unhappy ever after," and these are called tragedies. Apart from each character's individual problems, many stories have a "story

problem" that affects or involves most people in the story world.

The various characters in a story represent different drives within the story mind. We can say that characters have different perspectives on the story problem. They have different thoughts and feelings about the problem, and are naturally inclined to take different approaches to the problem.

This view of story may feel a little strange, if you are the kind of writer who first develops characters as authentic people and only then imagines what type of plot might emerge as a result of them pursuing their own, individual goals.

Using Dramatica theory involves taking a birds-eye view of a story. It asks you to imagine that the effort to solve the story problem will lead to interactions among various different drives within the mind as it seeks resolution. It suggests writers need to create characters to represent those drives, and that all the relevant drives should be represented in order for the cast to feel balanced.

Am I losing you so far? Because this is just the tip of the iceberg. Maybe I should stick with the parts of the theory that are more practical and less esoteric...

Using Dramatica Theory

The most useful components of Dramatica theory, in my opinion, are the ones that are easy for writers to grasp and offer the most immediate help with the process of creating better stories. These include:

The Basic Plot Elements

Dramatica theory identifies eight basic elements that make up a well-balanced and engaging plot, organized into opposing pairs (because it's the tension between pairs that creates drama).

Most other theories recognize one or two of these elements, usually referring to them as "the external goal" or "the story problem."

Dramatica is very useful in identifying a wider range of plot elements that add more nuances to your plots and generally make them more interesting. Including all eight elements makes it easier to create an "emotional rollercoaster" of a story -- that is, one with strong narrative drive. I've summarized these elsewhere in the article, "How to Create a Plot Outline in Eight Easy Steps."

Archetypal Characters

Dramatica theory identifies eight archtypal characters, each of which embodies some of the drives that should be represented in a balanced cast. These eight characters are easily recognizable to readers of genre fiction.

Of course, if you are writing a story that is more character-driven and you don't want the characters to seem too cliched, there are other ways of creating characters while still making sure the various drives are represented.

Act Structure

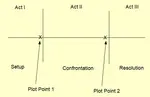

Most writers have been taught to write stories using a three-act structure, following in the school of Aristotle who said that every story needs a "beginning, a middle, and an end."

Of course, the three-act model has a couple of weaknesses. The second act of most good stories tends to be twice as long as the other two. And while stories usually have a major turning point at the divide between the middle and last acts, many people have noted that there is often another important turning point in the middle of the middle act.

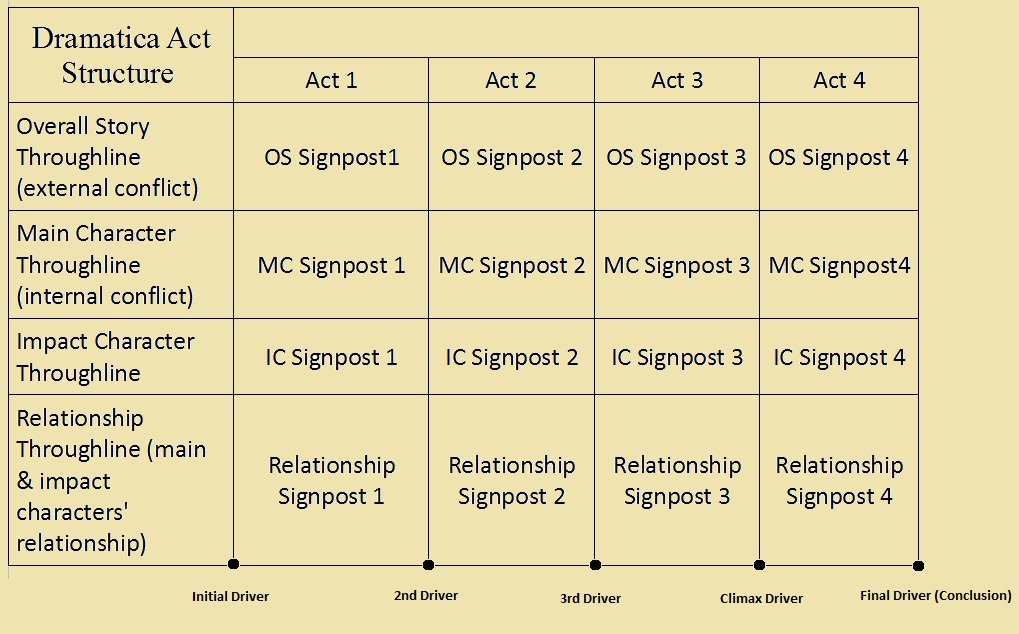

Dramatica theory posits a four-act model of story structure, which I find more accurate. In this model, each act begins and ends with a major turning point (for a total of five turning points). Moreover, dramatica explains that there is a shift in the thematic focus in each act, which another reason why each of the four acts feels different from the others.

Four Throughlines

Most theories of story structure note most stories have both an external plot and an internal plot. The internal plot involves the main character's personal conflict, how that gets resolved, and how or whether the main character grows and changes over the course of the story. Moreover, how this internal plot gets resolved generally affects the main character's ability to solve the story problem.

Dramatica goes beyong most models in arguing that well structured stories actually contain four throughlines. These are:

a. An overall throughline involving the story problem. This affects or involves most of the characters.

b. The main character's throughline, concerning their inner conflict.

c. An impact character throughline, concerning a character who influences the main character by offering an example of a different approach the main character might take.

d. A relationship throughline, which concerns the relationship between the main and impact characters and how it develops and is resolved over the course of the story.

Using dramatica theory, a writer will pay attention to developing all four of these throughlines separately and clearly. This tends to add more emotional depth to the story and increases its narrative drive.

Other elements

Dramatica theory describes many other elements (some 96, depending how you count them), which can be useful for a writer to illustrate or include in a story. Nonetheless, the complexity makes the theory cumbersome for even a dedicated plotter to wield, taking your focus away from other aspects of the story, such as authenticity. It can be a bit like trying to dance a ballet while simultaneously doing the job of the every musician in the orchestra, the stage manager, the house manager, and the valet in the car park. Dramatica also has a complex concept of how the four throughlines evolve throughout the four acts, how characters interact, and many other aspects of storytelling.

Luckily, using dramatica theory does not require a complete understanding of its many layers. However, if you are interested in learning a lot more, the best authority on the subject is its co-creator, Melanie Anne Philips and her Dramaticapedia and Storymind websites.

Be warned, however, the deeper one goes in the theory, the fewer stories one is actually likely to finish writing. It's a rabbit hole you can easily get lost down. If you want to be a fiction writer, you are better off taking small bits of the theory as you need them to stimulate ideas or fix story problems (which is my focus on this site).

- Home

- Story Structure

- Dramatica Theory