How to Structure a Novel

By Glen C. Strathy

Here we will review the basics of how to structure a novel for those who are new to the topic. While the most effective structure for your particular story may be simple or complex, depending on your genre and audience, all good stories are structured according to a few basic principles which we will cover below.

Beginning with Aristotle

Aristotle (Line engraving by P. Fidanza after Raphael Sanzio)

Aristotle (Line engraving by P. Fidanza after Raphael Sanzio)The first person to study the structure of good stories was the Greek philosopher, Aristotle, in his book Poetics, which he wrote around 300 BCE. Aristotle based his theories on Greek drama, particularly tragedy, which was an important form of storytelling at the time. (The word "tragedy" literally means "goat song," because the prize for the best play at the annual Athenian drama festival was a goat.) For many centuries, Aristotle was the only guide writers had on the subject of story structure, but his observations are as valid today as ever. So let's start by reviewing some of Aristotle's basic points.

1. Every good story has three parts: a beginning, a middle, and an end.

To me, this first observation seems blindingly obvious. However, many beginning writers will attempt to write a story without a proper ending or beginning.

So here are reasons why these three parts matter...

A good beginning tells the reader what the situation is, the state of the world before everything changes. It introduces at least one character (a protagonist or main character) readers can get interested in and shows what they are unhappy about or what they want. Most importantly, it gets the readers engaged by introducing a change in the status quo. Some new problem or challenge will arise and it makes the readers want to see how the characters will deal with it.

A proper ending shows how the story problem has been resolved, and whether the new state of the world or the character's life is better or worse as a result. It answers all the questions that arose in the story. It makes the story meaningful by showing how this new status quo is the result of the characters' choices and actions.

The middle is often overlooked but it is where the bulk of the story happens. The middle shows the journey from the situation at the beginning of the story to the situation in the end. It shows how the characters deal with the story problem, step-by--step, how they cope with the challenges along the way and how they grow.

Aristotle's claim that every good story has three parts (beginning-middle-end) is the reason many writers today rely on a three-act model story of story structure. As we will see, however, better models exist today.

2. A story is a series of events linked by cause and effect.

There are two parts to this observation...

a) Events.

First, "a story is a series of events."

You may ask "What is meant by an event?"

The best definition I have come across is that an event is an irreversible change that is significant, meaningful, and sends one or more characters in a new direction.

For example, an event such as, "the sun rose one morning," would not be a good event in a story. It's reversible, since the sun will simply set again that night. It's not terribly significant or meaningful, because its ordinary. The sun rises every day. And no one's life will be sent in a new direction because the sun rose.

On the other hand, consider an event like, "Ann discovers her best friend has betrayed her." This event is irreversible. Ann can't un-discover the betrayal. It's significant, because (one presumes) it's not something that happens every day. It's meaningful, because it is a major change in an important relationship. And it will likely send Ann in a new direction. Perhaps she will be looking for a new best friend. Perhaps she will be driven to revenge.

Similarly, a positive event such as a character winning a lottery, getting into the university of their choice, or meeting the love of their life will change their life going forward in meaningful, significant, and irreversible ways.

In addition to external changes, events can be internal changes, such as a character making a decision, coming to a new realization or insight, experiencing an epiphany, or changing her mind.

However, whether internal or external, an event MUST be a change. You can't describe a situation or state and call it an event. Something must change. Something must be different afterward. And each event or change must send the story in a new direction.

b) Cause and effect.

The second part of Aristotle's observation is that the events of a story are "linked by cause and effect."

In other words, the events of a story are not random or haphazard.

"This happens, and then this happens, and then this happens, etc." is NOT how to structure a novel or any story.

In

a well-structured story, each event is caused by the one before and in

turn causes the subsequent events in a definite chain reaction. The

chain of action and reaction helps create narrative drive. The reader

keeps reading to find out what will happen next as a result of what just

happened.

The only exceptions to this are...

a) The first event in the chain, the event that sets the story in motion, can be the result of luck or coincidence. Sometimes a character just happens to be in the right place at the right time.

b) The final event brings the series of events to a close. It creates a sense of completion. Ther reader is no longer wondering what will happen next, because a new status quo has been established.

3. A story shows a change in fortune for the protagonist.

A good story is about an important change in someone's life. Sometimes the protagonist or main character will begin the story in a miserable state and end up happy. In Aristotle's time, such stories were called "comedies."

In other stories, a character may begin happy or ambitious and end up destroyed. We call these "tragedies."

And there are some variations. Sometimes a character may save the world at the cost of their own happiness. Sometimes a character may fail to save the world, but personally end in a happier place than where they started.

Regardless, this third observation implies that a story is one big event, one big, irreversible, significant, meaningful change, made up of a series of smaller events.

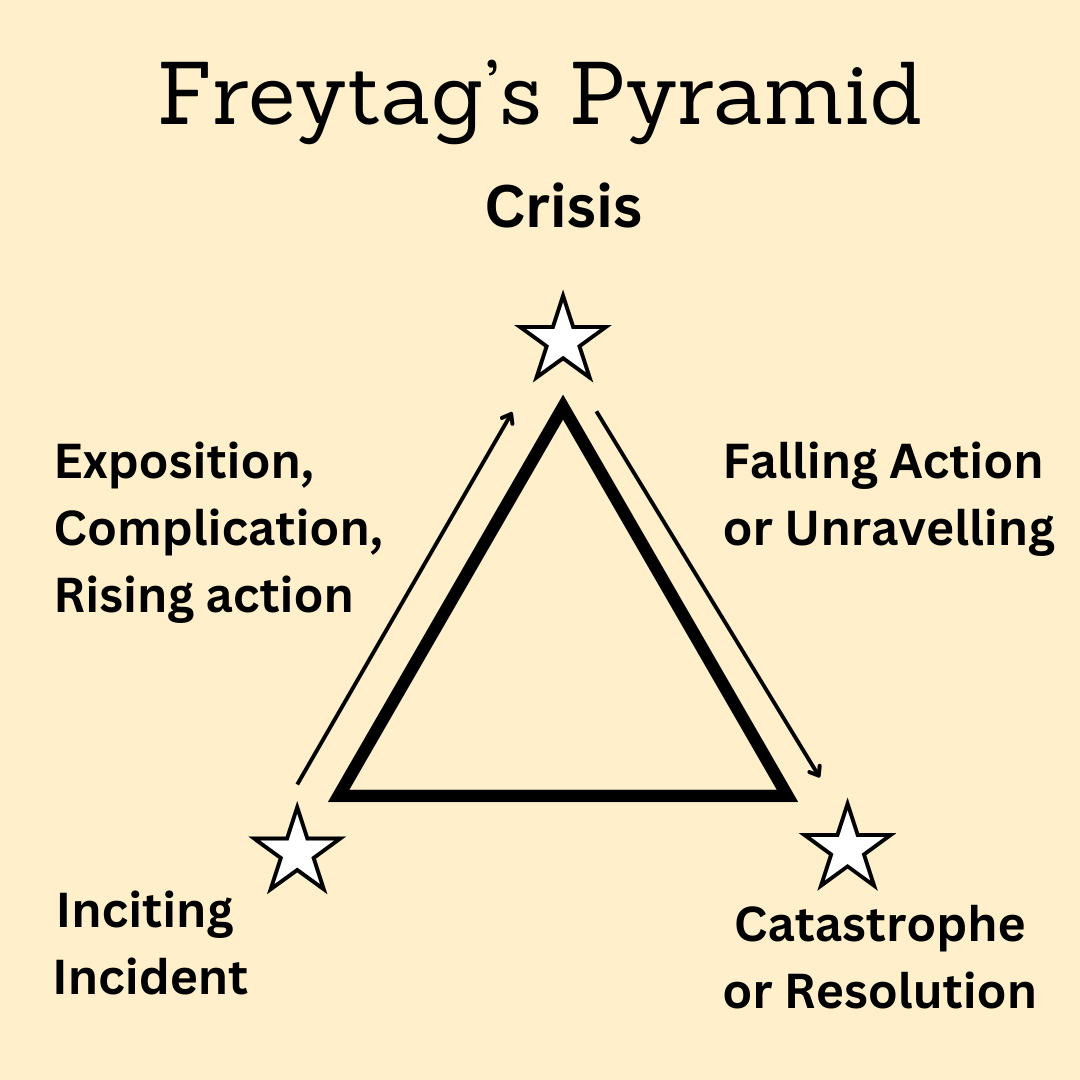

Freytag's Pyramid

For many centuries, Aristotle was the main authority on how to structure a novel (or any story). Then, in 1863, a novelist named Gustav Freytag combined some of Aristotle's other observations as well as his own and created a model for how to structure a novel which became known as "Freytag's Pyramid."

As you can see, Freytag's Pyramid is a five-part structure. This may be in part because Freytag had access to many more stories than Aristotle, including the plays of William Shakespeare. (Shakespeare wrote all his plays in five acts.)

The five parts of the pyramid are:

1. The inciting incident.

This is the event that ignites the chain of events that make up the rest of the story. It is the event that disrupts the status quo in the life of the main character or the story world.

2. Exposition, complication, and rising action.

This is the middle of the story. In a story with a happy ending, this part will introduce many complications as the characters try to address the central problem of the story. Obstacles will arise and the situation will get more difficult and challenging as the story builds toward the crisis. In a tragedy, the protagonist will make a lot of progress toward their goal in this section. They will have a series of ever greater victories. Also, the middle will contain "exposition" (the discovery of information) as the characters and the readers learn more about the problem, the motivations of other characters, and aspects of the story world they were unaware of before.

3. The crisis.

The crisis is the biggest turning point in the story. In a story with a happy ending, the crisis will be the moment in which the situation is "darkest before the dawn." It will be the moment when the story problem appears unsolvable. The main character's goal appears unachievable. Disaster seems inevitable.

In a tragedy, the crisis will be the moment when the main character seems on top of the world, certain to achieve their greatest ambition... before a crucial mistake or a fatal character flaw causes things to go wrong.

4. Falling action or unravelling.

In a tragedy, the moment of triumph at the crisis is followed by a reversal of fortune. All the main character's achievements unravel. Everything turns from good to bad to worse.

In a story with a happy ending, the falling action is the part of the story where the main character finally gains a key insight, makes an important decision, or otherwise takes control of the situation and starts winning. There may be a series of victories building to the final part.

5. Catastrophe or Resolution

A tragedy will end with a catastrophe. The protagonist will suffer the ultimate defeat, often losing what is most valuable to them -- perhaps their life.

In a story with a happy ending, the final event will be a resolution in which the protagonist achieves their ultimate victory, the successful resolution of the story problem.

Freytag's Pyramid has a couple of limitations. For instance, its shape implies that the events following the crisis should take the same number of pages as the ones before. This is incorrect. In a good story, most of the story leads up to the crisis. What comes after the crisis is usually much shorter. Also, the pyramid has only three main turning points, and most stories have more. For these reasons, writers have sought better models of how to structure a novel.

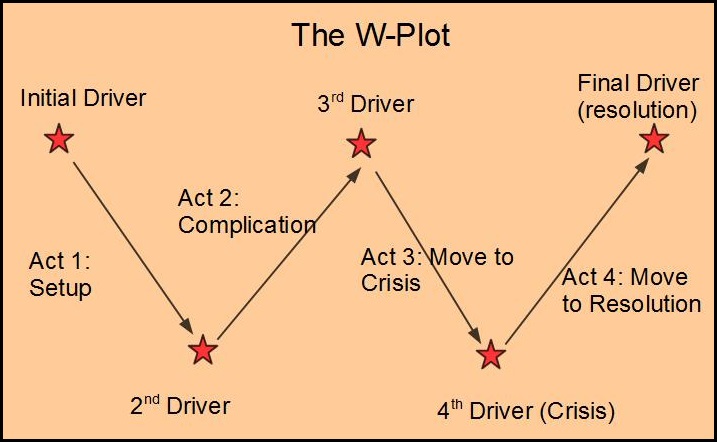

The W-Plot

The best model of how to structure a novel, in my opinion, is called, "The W-Plot." I first encountered it in Mary Caroll Moore's 2011 book, Your Book Starts Here, though it resembles other four-act story models. I have adapted it a little, combining it with some ideas from Dramatica theory and other sources.

As you can see, it looks like a "W"...

The W-Plot contains four acts that follow the basic pattern of a dramatic arc:

setup --> complication --> crisis --> resolution

Each act begins and ends with a major turning point or driver (to use a dramatica term). You can think of them this way...

Initial Driver: similar to Aristotle's "inciting incident." This is the event that ignites the chain of events that makes up the story.

2nd Driver: things get more serious here. In an adventure story, this is the point at which the hero embarks on the journey. In a romance, it may be where the relationship first turns romantic. In a mystery, it is the point where the detective discovers the case is more complex than it initially seems.

The 3rd Driver is sometimes a "point of no return," after which it is too late for the hero to back out of the journey or effort they are pursuing. In most genres, things get even more serious at this point. From here on the plot builds toward...

The 4th Driver is what Aristotle called "the crisis." It is the point of greatest joy or greatest dispair, depending on the story. At this point, things will start to reverse toward the resolution.

Final Driver: this is the event that establishes decisively what the outcome of the story will be. If, at the crisis, everything looked bleak, the final driver will be a victory. If, at the crisis, the hero was on top of the world, the final driver will be a disaster.

I would argue the W-Plot is the most accurate way to understand story structure. Once you start paying attention, you can find the W at work in all well-structured stories.

That said, plenty of variations exist, depending on your genre.

How to Structure a Novel That's More Complex

The genre, readership, your personal taste, and the particulars of the novel you are writing will determine how complex your plot should be to tell the story effectively. Sometimes, a simple chronological plot is best because it lets you focus on other aspects of the story (ideas, characters, setting, themes, etc.) Sometimes a more complex plot allows you to tell a more engaging story.

If you're curious about how to structure a novel with a more complex plot, here are a few approaches to bear in mind...

Multiple Story Arcs

In addition to the main plot (sometimes known as the external or overall plot), there may be a number of other plotlines or arcs running through a novel. Not all of them will be developed equally. Nonetheless, like the main plot, subplots and arcs should also be...

a) A complete dramatic arc. They will follow the pattern of setup --> complication --> crisis --> resolution. That implies that they will be comprised of at least 3-4 events or turning points.

b) Linked by cause and effect.

Some of the plots and arcs you may wish to develop include...

- The main character's inner conflict. If the main plot focuses on an external problem that involves the world of the story, the main character's arc will focus on the main character's inner problem. Who is this person? How will they be pressured to grow or evolve? What choice will they make at their personal crisis? Who are they in the end?

- The impact character arc. The impact character is someone who will influence the main character, typically by providing an example of a different approach to dealing with problems. This person will force the main character to doubt themself, which creates the main character's inner conflict. Make sure the impact character's story is also structured well and in a way that will affect the main character who is seeing it unfold.

- The relationship arc. Generally, the relationship between the main and impact characters will have its own arc. The relationship arc will be concerned with how the relationship forms, develops, reaches a crisis, and either ends up intact or with the characters separated.

- Subplots. Subplots can be used to explore the relationship between two minor characters or to explore a theme from a different angle or in a different set of circumstances. In some novels, the subplots are so well developed it is hard to decide which is the main plot.

Multiple Point-of-View Characters

The main character is often referred to as the "primary point-of-view (POV) character." The reader generally sees the story through the main character's eyes. However, many novels alternate among multiple POV characters, so the reader sees different events of the story from other character's perspectives. This may be done for a variety of reasons, such as to create dramatic irony, to give different types of readers someone they can identify with, or to explore different aspects of a theme. Many romance novels, for example, are written from the POV of both the male and female romantic leads.

When considering how to structure a novel with multiple POV characters, there are a few things to bear in mind...

1. Every POV character is the protagonist of their own story. They may have their own internal as well as external conflict. Their stories should also unfold in a dramatic arc (setup --> complication --> crisis -- resolution).

2. Not every POV character needs to be equally well developed. Sometimes, you may shift to a minor character's POV simply to let the reader see something the main character cannot. You may devote far more page space to one character than another. On the other hand, you may develop several POV characters equally, giving the novel multiple main characters. (Of course, that would mean each POV character would resolve their conflict in a way that determines the story's outcome.)

3. Each POV character's story should unfold (chronologically) in parallel. Of course, you may not tell the story chronologically...

Non-Chronological Storytelling

Many novels are written with the events in chronological order--beginning with the initial driver and proceeding step-by-step to the final driver and outcome. That is how to structure a novel in most popular genres.

Others novels are written in non-chronological order. There are a couple of reasons for doing so.

Obviously, the beginning of a novel needs to hook the reader. It needs to get the reader engaged enough in the story to want to keep reading. However, sometimes the start of your story is not very engaging.

One way to overcome this problem is to begin the novel at a more engaging part of the story. You might begin at the crisis and then jump back in time and tell the events of the story that lead up to the crisis, and then tell the ending.

Or you might start at the ending (if the ending is intriguing), and then jump back in time and tell the events that lead up to the ending.

In literary fiction, it is common to have non-chronological character arcs. You might introduce a character in a way that creates some mystery ("Why is this person like that?"). It might be near the character's personal crisis or the complication part of their journey. Later, you may insert a flashback that shows how that character's arc began.

A tip on how to structure a novel in non-chronological order: Try to get the chronology clear in your mind. Map out the events on a timeline and make sure each arc or plot makes sense and would be engaging if it were told in chronological order. It helps to write each event on an index card.

Once that's done, you can rearrange the events (cards) in the order you want to present them in the novel and use this as your guide when writing.

For more on how to structure a novel, check out some of the articles below or on this page.

You might also enjoy this article on how to write a prologue (and whether you need one).

- Home

- Write a Novel

- Novel Structure