How to Write a Romance

By Glen C. Strathy

I will confess upfront, romance is not my favourite genre. If you're still reading, and wondering why I would be giving tips on how to write a romance despite my own bias, the answer is... because there's money in it. Roughly half of all published novels are romances, which tells you the readership is huge. Moreover, for fans of the genre, romance novels are fun to read and write. They don't require as much in-depth research and world-building as historical fiction, high fantasy, techno-thrillers, or science fiction, nor the sophisticated prose and complex themes of literary fiction. Romance novels are more formulaic than some genres, which makes them a little easier to plot. So if you like the genre, it's worthwhile learning how to write a romance.

Of course, it takes talent and skill to write a romance worth reading, like with any other genre. So let's look at the unique features romances, before turning to how to write a romance plot.

What is Romance?

I'm sure you already know that romance novels are love stories. But characters form romantic relationships in many genres. For a novel to be considered a romance, it must meet certain other criteria. Most importantly...

A romance is a story about a character finding true love.

The main character and her love interest must fall in love over the course of the story. Moreover, they must be alive, in love, and together at the end of the story. Shakespeare's Romeo & Juliet, for example, would not be considered a romance in today's world, because the lovers die before the play ends. If a story ends with the couple separated, no longer in a relationship, or even having serious misgivings about their relationship, it is not a romance.

Traditional romances end with the two lovers married or at least with a strong implication that they will be together from then on. Modern romances, and especially young adult romances, don't require couples end up "happily ever after," but they must at least end up "happy for now."

Romance is primarily a female genre.

Second, though it's not strictly required, the main character in almost all romances is female. While some men read romance novels, roughly 80% of romance readers are women. Readers want a female main character because they enjoy imagining themselves in her shoes. The exception is male-on-male gay romances, but that is a subgenre.

A romance story is an emotional experience.

Your primary consideration when you write a romance is to give the reader the vicarious emotional experience of finding true love. Your heroine needs to be someone the reader can imagine being. Readers want to ride the emotional roller coaster of the heroine's feelings from the first to the last page. And they want an emotional payoff of happiness and satisfaction in the end.

If this seems a bit idealized, that's because it is. Romance is all about escapism. It's about giving the reader an emotional workout she may not be getting in her everyday life. That doesn't you should dispense with realism and authenticity when you write a romance. But a romance story cannot get bogged down in areas that detract from the emotional experience.

Romances feature relatable heroines and idealized love interests.

Because romance is escapist literature written mainly for women, the lead character in most romances tends to be an "everywoman" -- someone fairly typical for her age and gender.

You want to write a romance heroine who your typical reader can relate to, and someone she would enjoy imagining herself being or how she would like others to see her. So romance heroines tend to be...

- Smart and articulate, with established interests, but not so nerdy or intelligent that average readers can't relate to them.

- Strong and independent, but not to the point that they have no desire for a relationship.

- Nice -- at least not overtly immoral, criminal, or low-life. Your heroine can't steal another woman's man or do things the reader would strongly disapprove of.

- Nice looking, but in an average way. (Most women don't relate to women with the kind of supermodel or playboy bunny looks men fantasize about. In fact, overly attractive women are often seen as less likable.)

- Financially stable. At least in contemporary romances, heroines tend to have successful careers, and the kind of careers most women can imagine enjoying. (Some romances feature heroines who leave an unsatisfying career for one more meaningful.) At any rate, today's heroines aren't looking for a husband to support them -- though a wealthy love interest would be a bonus.

Similarly, your heroine's love interest should be the kind of man most readers would be drawn to -- to the point of being somewhat idealized. Traditionally, male romantic leads have tended to be alpha males who are ...

- Physically attractive to both the heroine and perhaps other women, so it is more flattering for the heroine when he chooses her above all others.

- Rugged or athletic.

- Smart (but again, not nerdy).

- Charming.

- Confident.

- Generous.

- Intuitive (especially about knowing what the heroine wants and anticipating her needs).

- Emotionally mature (never loses his cool).

- Financially stable (successful in his career, or perhaps wealthy) -- though he could be in the process of building a new enterprise, which will naturally succeed.

- Courageous.

- Decisive, with a tendency to take charge of a situation and solve problems when the heroine is at a loss.

- Either a leader or independent loner (not a follower of others).

- Protective. He should be able and willing to defend the heroine when she wants to be defended, while also knowing when she would prefer to fight her own battles.

- Someone who needs a woman (like the heroine) to fill a gap in his life or offer him the kind of insight or help he needs.

Of course, not every woman is attracted to the same type of man, so there is a range of different love interest types. But a good love interest should not have too many traits average women find unattractive, such as being controlling, chauvinistic, or self-centred.

A love interest should also need the heroine to help him grow. E.g. he could be a "bad boy" in need of the right woman to help him reform. Or the heroine could be the first woman to challenge him intellectually or force him to rethink his outlook.

The Four Major Arcs in a Romance Novel

The best ideas for romances may come from your own life experience or that of your friends and family. However, when you write a romance based on real-life events, you will probably need to heighten the drama so they deliver the type of emotional experience readers expect.

If you're stuck for ideas, or you're looking for ways to kick your story up a notch, you may want to explore some of the more common types of romance plots, which I've covered in another article.

Assuming you have an idea already, here's how to structure a romance story...

How to Write a Romance: Privilege the Relationship Arc.

You may know from other articles on this site that stories have four kinds of story arcs or throughlines:

- The Overall Throughline, which concerns a problem that affects or involves all the characters.

- The Main Character Throughline, concerning the main character's inner conflict.

- The Impact Character Throughline, concerning another character's influence on the main character.

- The Relationship Throughline, concerning the relationship between the main and impact characters.

The first secret of how to write a romance is that the Impact Character will be the Main Character's love interest.

The second secret of how to write a romance is that the Relationship Throughline will be the most prominent while the Overall Throughline will take a back seat.

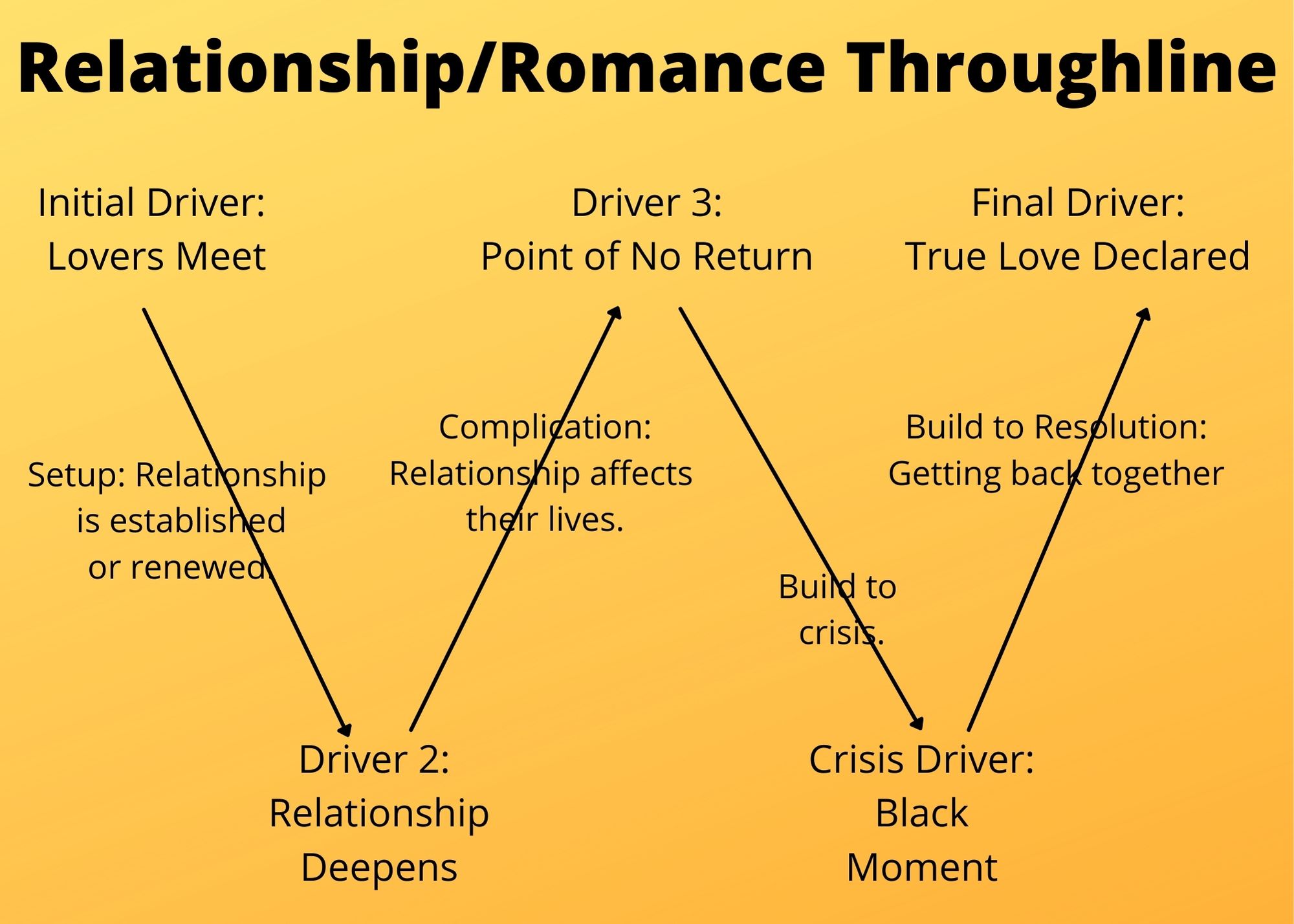

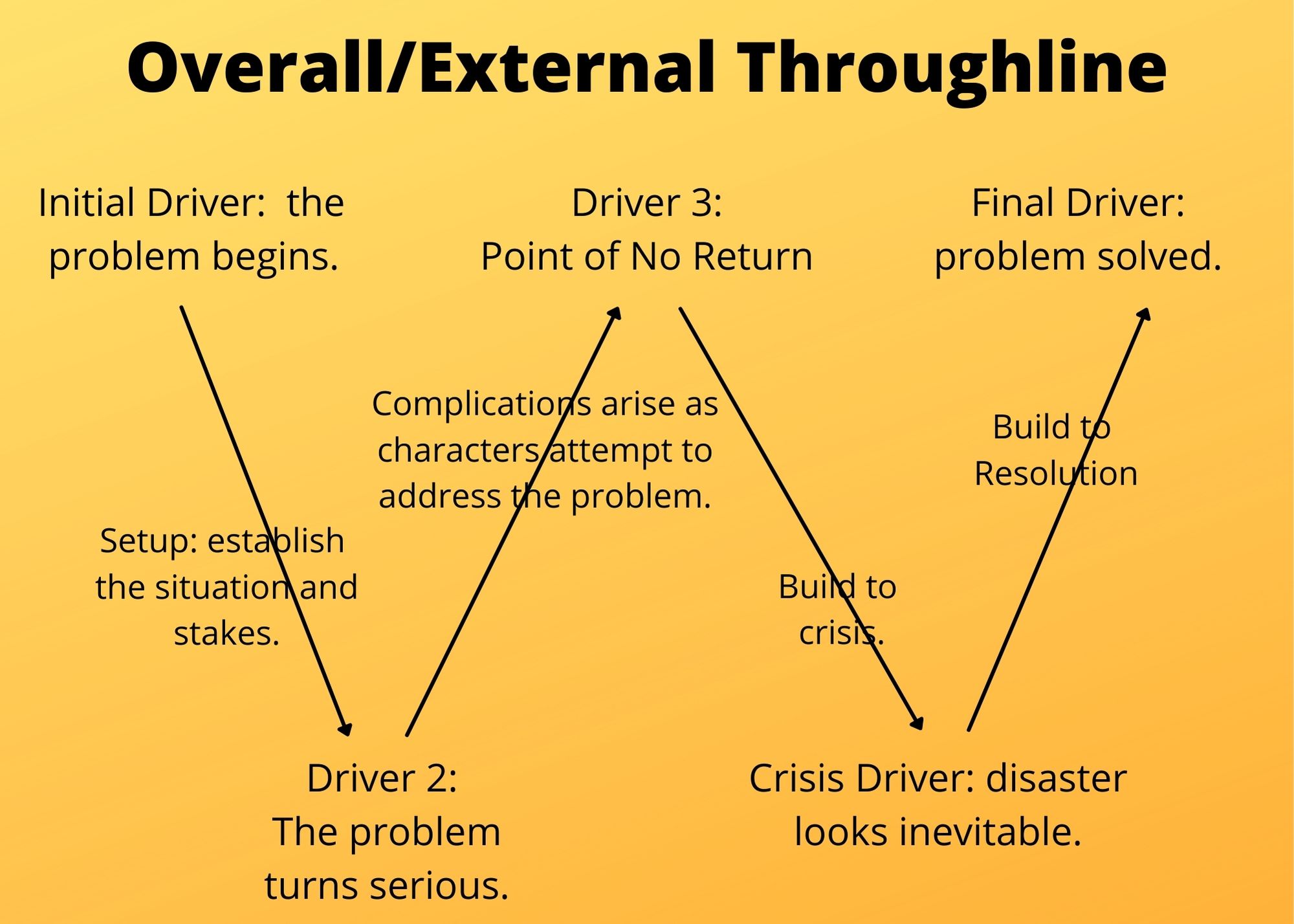

So, given how important the Relationship is, let's look at how the structure of the Relationship story unfolds when you write a romance, using the 4-Act W-Plot model...

In this model, each of the four lines represents an act, and each act begins and ends at a major turning point, or "driver." Let's go over each of these.

Initial Driver: This is the event where the lovers meet for the first time in the story. It's not necessarily the first time they ever met. They could be old friends, friends of friends, or perhaps they dated in the past. They could even start out as established enemies or rivals. But you begin the story of their romance with this first meeting. The initial driver should happen before the end of chapter one. In many romance lines, readers expect the couple to meet on the first page.

When you write a romance, it's a good idea to give your lovers a "meet cute," an amusing way for them to run into each other. Imagine that, years from now, the story of their meeting will be something they can entertain friends with. They could meet because of a funny coincidence or accident. Or perhaps they find themselves in an upsetting or embarrassing situation in which one of them behaves badly and later regrets it. It doesn't matter whether this first meeting makes them like or dislike each other, as long as they notice each other. The incident should be memorable.

Act 1 (Setup): In the first act, you want to get your lovers interacting in some way. Put them in a situation where they must talk to each other or perhaps do something together, whether willingly or with reluctance. It helps to give the reader some sign that these two might be good for each other, even if they don't see it themselves.

Driver 2: With this event, the relationship deepens. How this works depends on the type of Romance you are writing. In a sweet or Christian romance, this might be where they first realize they are attracted to each other. It might be the moment when they have their first kiss. In a steamy romance, it might be where they have sex for the first time. Either way, the relationship changes here, becoming romantic or intimate.

Act 2 (Complication): In the second act, the fallout from the new relationship creates new complications in their lives, which can be both pleasant and troublesome.

Driver 3: With this event, the relationship crosses a "point of no return." The two lovers bond in a way that seems deep and permanent. The heroine may realize she is in love. They may confess their deepest thoughts and feelings to each other like they have never done with anyone. If it's a steamier romance, they may have the best sex ever.

Act 3 will then build toward a crisis. A potential threat to the relationship will arise and grow stronger. One person's fear of commitment or their painful past may be triggered, causing them to sabotage the new relationship. Someone's past lover might return, or a new rival may appear. Some information may emerge that casts a bad light on one of the two lovers, causing the other to have doubts. One lover may have chosen to hide some information from the other that will be upsetting when it is revealed. One person may resist altering their life to accommodate the other. External forces or circumstances may threaten to split them apart, etc.

Crisis Driver: Sometimes called the "black moment," this is the turning point where the relationship breaks down and the lovers separate.

Act 4: The effects of the crisis are felt... and then act builds toward the moment when the two lovers reconcile.

Final Driver: This is the moment of reconciliation when the two lovers finally declare their love for each other and happiness is achieved.

How to Write a Romance: Include an External or Overall Story

With the relationship arc taking centre stage, the external or overall plot may be simplified. Nonetheless, it should be present, if only to give the two romantic leads a reason to interact -- especially if they are two people who would normally never interact. Examples of typical overall story problems include:

- Saving something -- a business, a small town, a family farm, an endangered species, a school, a tradition etc.

- Solving a mystery, catching a criminal or spy, etc.

- Going on a worthy mission or adventure.

- Being trapped in a situation that requires cooperation to escape.

- Fulfilling someone's dream or a promise.

- Finding a lost treasure.

- Coping with issues concerning friends, career, family.

- Winning a contest, a bet, a job, or something else.

- Recovering from a tragedy.

- Saving someone's reputation.

As you can see, the overall plot of a romance may borrow from other genres (mystery, thriller, adventure, women's fiction, etc.). Sometimes the two lovers will come at the problem from different directions or they may champion different solutions. They may initially be adversaries or rivals. In other cases, one person may be reluctantly dragged or pressured into helping the other person solve the story problem.

The structure of the overall throughline is similar to that of the relationship, and unfolds in parallel to it. Using a 4-act structure, it looks like this...

How to Write a Romance: the external story will not be the main focus, but it still needs to be developed.

How to Write a Romance: the external story will not be the main focus, but it still needs to be developed.In Act 1 (Setup), the story goal is established, along with the

reason why this goal is important to the heroine or possibly her love

interest. This is the story problem. In addition, the basic situation and players are introduced.

In Act 2 (Complications), the characters make an effort to accomplish certain tasks or objectives that will lead to the achievement of the goal. At the same time, opposing forces, difficulties, or events arise that undermine the efforts to achieve the goal.

In Act 3 (Move to Crisis), the tension builds (will the goal be achieved or not?) leading up to an event in which it seems clear that the effort has failed. The crisis is the point where things are "darkest before the dawn."

In Act 4 (Move to Resolution), the main character will have a realization or change in tactics that will let her seize control of the situation and bring about the successful attainment of the goal.

In other words, the Overall Throughline in a romance is much the same as any other story. The difference is that, when you write a romance, you do not devote nearly as much space to narrating the overall throughline as you do to the relationship throughline. Each part of the Overall Throughline may be shown only in a brief scene or two, or as part of a bigger scene in which other things happen. The initial driver of the Overall Throughline may take place off-page, before the story begins.

However, it's important that you include the Overall Throughline because it is a source of narrative drive, and it will give the lovers an on-going reason to interact, even after they have broken up (which can be very useful in act four, when you are looking for a way to get them back together).

How to Write a Romance: the Main Character's Inner Arc

Next to the Relationship Throughline, the main character's inner conflict is most important. The main character's inner conflict and how she resolves it will determine whether the relationship succeeds (it will) and whether the overall story problem is solved (typically, it will be too).

It's a good idea to ask yourself why, at the start of the story, your heroine has not yet found true love. What is holding her back? Does she have an attitude, a philosophy, a habit, a bad experience, or a way of doing things that is standing in her way? Is she too devoted to other pursuits to have time for romance? An important element in the story will be how she overcomes this challenge by growing, changing, or perhaps finding a lover who changes for her.

Your main character's arc will also progress in four stages and run parallel to the relationship and overall throughlines.

1. Initial Approach

Show the reader who the main character is at the start of the story. Have her cope with a small problem or situation using her usual approach (the one that's holding her back). The reader needs to get a sense of who she is, like her, and yet also see that she may have a problem.

Also in the first act, let your heroine see her love

interest using a very different approach to handling a problem or a

situation. This is the first time she sees anyone taking this approach

and it may surprise and intrigue her, especially if it seems to work for

him. This is the start of his impact on her.

2. Growth

In the second part of the story, your heroine should feel increasing pressure to change. Perhaps an event happens in which her approach doesn't work. Perhaps she starts to see how she's been holding herself back. At the same time, she is observing how her love interest does things and learning how he thinks. He may encourage her to take his approach, and she may experiment with it in a small way -- like trying on a jacket to see if it fits.

3. Personal Crisis

In the third act, you want to ramp up pressure on your heroine to change. Perhaps her love interest will present his strongest argument in favour of his approach. This doesn't mean he will try to make her change. He may just tell her his thoughts about an important experience in his life. Or she may see him using his approach to deal with a high-stakes situation, so that she is forced to think more seriously about it. Then put your main character into a situation where she must decide whether to double-down on her established approach or take a leap of faith and adopt his approach. She may do this after the black moment or the crisis in the overall story have made seem clear that her old approach is not working.

Since you are going for a happy ending, whichever choice your heroine makes -- whether to adopt her love interest's approach or double-down on her established approach -- it will be the right one. The approach she chooses will let her solve the external problem, find true love, and end up happy. If doubling-down is the right choice, her love interest will give up his approach and adopt hers. Either way, they will end up on the same page.

4. Judgement

In the end, show how your main character and her love interest are better off because of the choice she made. Create a scene(s) or event(s) that shows the reader that your heroine is happier, more content, more at peace -- and not just because she now has her man. Do the same for her love interest. Show them happy together.

How to Write a Romance: Give the Love Interest His Own Arc

An author will typically write a romance novel using two point-of-view characters -- the heroine and her love interest. While the heroine is the main character, much of the story will also be told from the love interest's perspective. (I suspect this is done because everyone wishes they knew what their crush is thinking, so this is another form of wish fulfillment fantasy.)

Every point-of-view character is to some extent the main character of their own story, which means the love interest in a romance is like a second main character. He will have his own inner conflict that will require him to grow in order to find true love with the heroine. In a good romance, while he is having an impact on the heroine, she is having a similar impact on him, showing him an example of a different, perhaps better approach to handling certain situations.

One secret to making this work well is to give each of the two romantic leads a different inner conflict -- that is, a conflict over a different issue.

For instance, let's say you decide your heroine's inner conflict is one of control vs. giving up control. Maybe she is someone who always tries to control every situation, but she learns from her love interest that sometimes giving up control can work better, and that's what makes the new relationship work and lets solve the story problem. So far, so good.

But don't make the love interest's growth be the reverse of this. Don't have him be someone who always gives up control and has to resolve his inner conflict by learning from the heroine to take control of situations. That would be redundant.

Instead, give the love interest a slightly different inner conflict. Have him learn a different lesson from her example.

For instance, if your heroine's inner conflict is over having control, maybe her love interest can be someone who takes chances even when the odds are against him and needs to focus on endeavours where the odds are in his favour. Maybe his biggest problem in life comes from his refusal to accept certain realities, and he needs to learn from the heroine how to accept situations better. Maybe he's always denying himself pleasure to focus on his long term goals, and learns from the heroine's example to benefit by giving in to a few temptations.

By making their inner conflicts different, you will make both characters more complex and make their relationship more interesting. Showing how each person offers the other an opportunity to grow shows they are suited for each other and will make a good partnership.

How to Write a Romance Publisher's Want

While the above is generalized information that applies to a wide variety of romances, you should know many subgenres and categories of romance novels exist.

Some romance lines are targeted to a specific age of reader. There are young adult romances for teenage readers, romances for women in their 20s who may be sexually active, and romances for women in their 30s or their 50s who are interested in more mature relationships.

Some romance lines have very little graphic sexual content. A Christian romance, for example, will have no sex outside of marriage. Other romances are so graphic they could be classified as erotica.

When considering how to write a romance that will fit a publisher's needs, check out the romance lines put out by the publisher. Decide which lines you would be most interested in writing for. Find out what the stories in that line have in common. Then tailor your story to fit that line's requirements.

Incidentally, one of the best ways to learn how to write a romance is to join the Romance Writers of America or go to their annual conference.