How to Begin a Novel: Where Should the Story Start?

By Glen C. Strathy

Deciding how to begin a novel (what point in the story to start) is a crucial skill for fiction writers for one very important reason. If the first chapter of a novel doesn't grab a reader's interest, they will likely stop reading.

Worse, agents and editors often decide to pass on a book based on just the first page or two. A weak opening can be the kiss of death for an otherwise great novel.

So lets look at some of the options for story beginnings, as well as some cliched openings you might want to avoid.

How to Begin a Novel: What The First Chapter Must Do

You can find exceptions to almost everything I'm about to suggest, except for this first point. There is one requirement a story beginning must meet, and that is ...

Good story beginnings entice readers to keep reading.

If the beginning of a novel captures a reader's interest enough to keep them turning pages, it's a good beginning. If it doesn't, it's not, and it's doubtful a publisher will be interested in the book either.

To begin with, here are some techniques you can use to make your beginning effective:

- Establish an intriguing narrative voice.

- Connect the reader to a sympathetic character in a predicament.

- Present an event (action or decision) that promises to ignite a chain of events with significant consequences.

- Create suspense or mystery.

- Introduce an intriguing idea, situation, or proposition that begs exploration.

Regarding mystery and suspense, here's how I define these words...

Mystery occurs when the reader anxiously wonders what has happened or what's going on. (For example, a character stumbles across a dead body, causing the reader to wonder who killed this person, why, and how.)

Suspense occurs when the reader anxiously wonders what will happen next. (For example, if a character receives a mysterious beeping package in the mail with instructions not to open it, the reader will start to wonder what's in it and what will happen when the package is opened.)

Other Helpful Things Beginnings Can Do

Story beginnings can do a number of other things to hook the reader. For instance, beginnings should, if possible...

- Make a promise (show what type of story the reader is in for).

- Establish the genre, tone, narrative voice.

- Introduce at least one character.

- Emphasize “scene” rather than “summary.”

- Establish an important setting.

A beginning can also...

- Establish a problematic relationship.

- Introduce an intriguing story world.

- Introduce a theme or philosophical perspective.

But don't feel your story beginnings must do all these things, or even most of them. The important thing is that they hook the reader. The above techniques, in any combination, can help with this.

Regarding the last item you don't see the philosophical opening as much today, but it can be found in many classic works. For instance, Pride and Prejudice begins with the narrator stating a philosophical premise...

"It is a truth, universally acknowledged, that a single man

in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife."

The rest of the novel then proves that statement by showing how all the single men end up with wives.

Five Ways to Begin a Novel

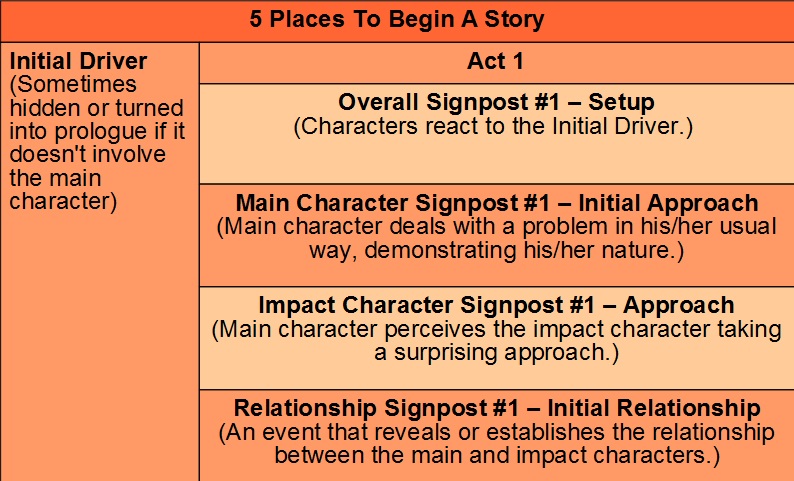

As you may know from elsewhere on this site, Dramatica theory states that every complete story has four throughlines.

The overall throughline, or main plot concerns the story goal, and affects or involves all the characters in the story world. It's an objective perspective on the story.

The other three throughlines are more subjective and concern the arcs of the main character's inner conflict, the impact character, and the relationship between the main and impact characters.

Assuming you're telling your story in chronological order, this model actually gives you five potential events you can begin your novel with. An event is an irreversible change that sends the characters in a new direction (and makes the reader wonder what will happen next as a result).

In other words, you want to begin a novel at a point where something happens. Something that will ignite a chain of events that will make up the story. Never begin with a scene in which nothing happens.

How to Begin a Novel Option #1: The Initial Driver

Let's say you want to start with your overall throughline (or external plot), which concerns the pursuit of the story goal. There are two possible points within this throughline where your story could begin.

You could begin with the initial driver -- the crucial event that begins the story and without which the rest of the story would not happen.

This is a valid choice, however there are reasons why you may wish to avoid it.

One reason is that the initial driver often takes place long before the main character enters the story. For example, in The Lord of the Rings, the initial driver is Frodo's finding of the ring, which happens many years before the novel begins.

In other stories, the initial driver occurs when the main character is too young to make the connection with the reader. In Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, the initial driver is Voldemort's attack on the Potter family in which Harry's parents are killed. Harry is only a year old at the time. So the reader doesn't properly meet Harry until a decade later.

The challenge is that many readers want to meet the main character on page one. If they don't, they may put the book down.

Writers sometimes address this by putting the initial driver into a prologue, which some readers will simply skip. (The absence of the main character in the prologue is one reason some readers hate prologues.)

Nonetheless, beginning a novel with the initial driver is a valid choice, especially if the main character is present for this event.

How to Begin a Novel Option #2: The Overall Throughline

The second option is to skip the initial driver, and begin the novel with the first Overall Signpost or the setup of the external story. With this option, the reader will see various characters reacting to the initial driver, but will not know what they are reacting to. For instance, in Harry Potter, the opening shows Vernon Dursley seeing all kinds of strange things -- a cat reading a newspaper, weirdos celebrating in the street and calling him a 'muggle' -- but he has no idea what has caused all this. This technique has the advantage of creating some mystery. The reader wants to keep reading to find out what has happened.

The writer can fill the reader in on the initial driver later in a flashback or through some other device.

Beginning at this point may be a good choice if the

protagonist is the main character and present for this event. However it is not absolutely necessary for the main character to be present.

How to Begin a Novel Without Preamble

Both the first two options involve beginning the novel with an event.

Try not to begin a novel with pages of exposition, backstory, or anything else that can be called preamble, especially if you are writing genre fiction. You don't want your reader thinking, "Is anything actually going to happen in this book?" Instead, use an event to start things happening right away.

Here are some types of preamble you should avoid beginning a novel with. They all work against you by postponing the reader's engagement...

- Lengthy physical description of main character.

- Lengthy character backstory.

- A journey to where the story begins.

- A flashback or dream sequence.

- The main character thinking, philosophizing, feeling.

- A tour/lengthy description of the main character's house/room.

- An insignificant day in a character's life or a character performing mundane activities.

Take note especially of this last point. There is a widely misinterpreted piece of advice given to writers that says a story should begin with "an ordinary day" in the main character's life.

The trouble is that most people's "ordinary" days are dead boring, and the last thing you want to do is make your first chapter boring.

One way to avoid preamble is to use a technique called in medias res.

I have discussed this at length in a different article. Briefly, it means to begin "in the middle" of the

action. Let the curtain rise on an event already in

progress.

How to Begin a Novel Option #3: Begin the Main Character's Arc.

If you are writing a more character-driven story, you may wish to begin with one of the character throughlines. For instance, you might begin with the main character throughline.

To introduce the main character and begin his/her arc, you will begin the novel with an event that shows who the main character is at the time the story begins. As the story progresses, the main character's arc will show how they are pressured by events to change. But before you can pressure them to change, you must establish who they are initially.

The best way to establish the main character is with an event. Personality is best revealed by actions. So show the main character tackling a problem in their unique way. Make sure something happens as a result of what they do. This will reveal and establish the main character's personality, skills, and typical way of approaching problems.

How to Begin a Novel Option #4: Begin the Impact Character's Arc

Another way to begin a novel is to introduce the Impact Character. The impact character is someone the main character sees who has a very different approach to tackling problems. The impact character makes the main character doubt their own approach.

Again, this should be an event. Something must happen, in the course of which the main character sees the impact

character tackling a problem in a way completely different from how the

main character would do it. This gives the main character a reason to doubt their own approach, which develops their inner conflict.

How to Begin a Novel Option #5: Begin the Relationship Arc

The fifth option is to begin a novel by introducing the relationship arc. This is the arc of the relationship between the main character and the impact character.

Again, you will establish this relationship with some event. Maybe they will start to like each other as a result of this event (in romance, this is sometimes called a "cute meet.") Maybe they will initially hate each other because of this event. Either way, this event will establish a relationship between them.

It may also be that the relationship was already established before the story begins. Perhaps they start as established friends, acquaintances, relatives, rivals, employer/employee, teacher/student, etc. You may just need an event to demonstrate what that relationship is, before it starts to evolve.

Avoiding Preamble To The Subjective Throughlines

Note that options 3-5 all require the main character to be present, thus satisfying the reader's desire to meet the main character quickly.

In most cases, you should begin a novel by introducing the main character, so the reader can get attached to this character. You want to avoid preamble that gets in the way of the connection between reader and main character being formed. Some examples of this type of preamble are...

- Lengthy history/description of setting (“infodump”).

- Pitch battle or intense action.

- Dialogue.

- Prologue.

- Opening in a minor character's perspective (especially one who quickly dies).

I know what you may be thinking. A pitch battle? Wouldn't that be a way to open in medias res? Isn't that a good thing?

If the action scene is the inciting incident, that can be an effective beginning for some readers. But other readers will not care about the action scene unless they connect with the main character in the course of that event.

Similarly, some readers dislike opening with dialogue -- unless they have first connected with the main character.

As for the last point (opening in a minor character's perspective), some readers feel it is a "bait and switch." It can be disconcerting to get attached to a character in the first chapter, only to have that character die and the story continue with the real main character.

So introduce your main character in Chapter One -- preferably on the first page.

Establishing The Reader's Connection With The Main Character

To create an empathetic connection between reader and main character as quickly as possible, you might...

- Open with the character's point of view and predicament.

- Create empathy by giving the character dilemmas, challenges, failings, worries, strengths, ideas, feelings, etc that the reader can relate to.

- Make the character admirable.

- Make the character likeable (charm).

- In genres defined by audience, make the character close in age and gender to the typical reader.

Most important... when you begin with your main character, don't start with an ordinary day in his/her life. Make it a day when something extraordinary happens to the character -- when they have to deal decisively with a tough situation or problem.

So create an event that lets the reader see the character's initial strengths, weaknesses, attitude, etc. Give the readers all the information needed to realize this is a character they want to spend time with.

How to Begin a Novel the Wrong Way

There are some story beginnings that most people use when they are just starting to write stories. Please note that there is nothing technically "wrong" with any of them. You will see plenty of published novels that use them.

The problem is that agents and editors also see lots of manuscripts that use these types of beginnings -- and by lots I mean thousands. When you're trying to sell a novel, you want to show the agent or editor right away that you have something original. So it may be best to avoid cliches. Here are some worn out types of openings...

- The main character wakes up

- The main character wakes up and goes through their typical morning routine (too much preamble).

- The main character wakes up and drives to work.

- The main character wakes up with amnesia or in a strange place. (Get the idea? Waking up is overused.)

- Moving day.

- A phone call.

- The main character stands before a mirror or wardrobe and thinks about her appearance (a not very subtle way to work in the main character's physical description, especially in first person).

- An alarm bell spurs the hero into action.

- A description of the weather.

- The main character weeping (an attempt to evoke curiosity).

- A writer stares at a blank page (wonder where that idea came from?).

- The main character stares out window and thinks/feels/reflects.

- The main character sits alone in restaurant/bar/cafe waiting for someone who is late.

Trouble Avoiding Preamble?

If you have a hard time avoiding preamble in your story beginnings, here are some suggestions...

- If it's a first draft: Don't worry. Just write the opening chapters with all the preamble you feel you need. But then...

- When you're revising your first draft: Go back and cut the opening pages up to the point where something interesting or important is happening.

- If you're afraid of cutting too much material from the beginning: Show both versions to different people and ask them which version makes them want to read on.

How to Begin a Novel in a Non-Chronological Way

I should also point out that not every story begins with the first act. Sometimes, if the start of a story is a little weak, a writer can compensate by starting at a more interesting point in the story (a flash forward) and then tell the beginning later.

For instance, let's assume the chronological arc of your story has four parts...

Setup --> Complication --> Crisis --> Resolution

You might decide to...

- Begin at the resolution, and then jump back and tell all the events in order that led up to the resolution.

- Begin at the crisis, then jump back and tell all the events that led up to the crisis. Then tell everything that happens after the crisis (the resolution).

- Begin at the complication, jump back and tell the setup, then jump forward and tell the crisis and the resolution.

Non-chronological story beginnings can have the added advantage of creating some some mystery, because the reader will not know what is going on at first and will be curious. It can also create some suspense, in that you can leave an event hanging while you flash back and show what came earlier.

- Home

- Storytelling Tips

- Beginnings